THE SCARAB

She finally meets the woman from downstairs that she’s heard crying from time to time. She’s coming out her garden gate and Pina, on her way to the cemetery, introduces herself before the lady can get away.

“Hello downstairs neighbor.” She speaks from a ten-foot distance on the sidewalk. “I’m Pina Trentini, the one you have to blame for all the noise above. I’m sorry about that. The virus has turned me a little crazy and I spend a lot of time up there walking in circles.” She wonders how it sounded below when she and Charlie ran around the apartment in Mexican wrestling masks, exercising their war chants, on the way to having loud sex.

The woman blinks her eyes and almost forms a smile. “You’re not so bad. I’m Sylvie Saunders.”

“You moved here recently didn’t you?”

“Just before the holidays. From Seattle, to be closer to my son and his family in San Francisco. Now I can never see them.”

“That must be so hard.”

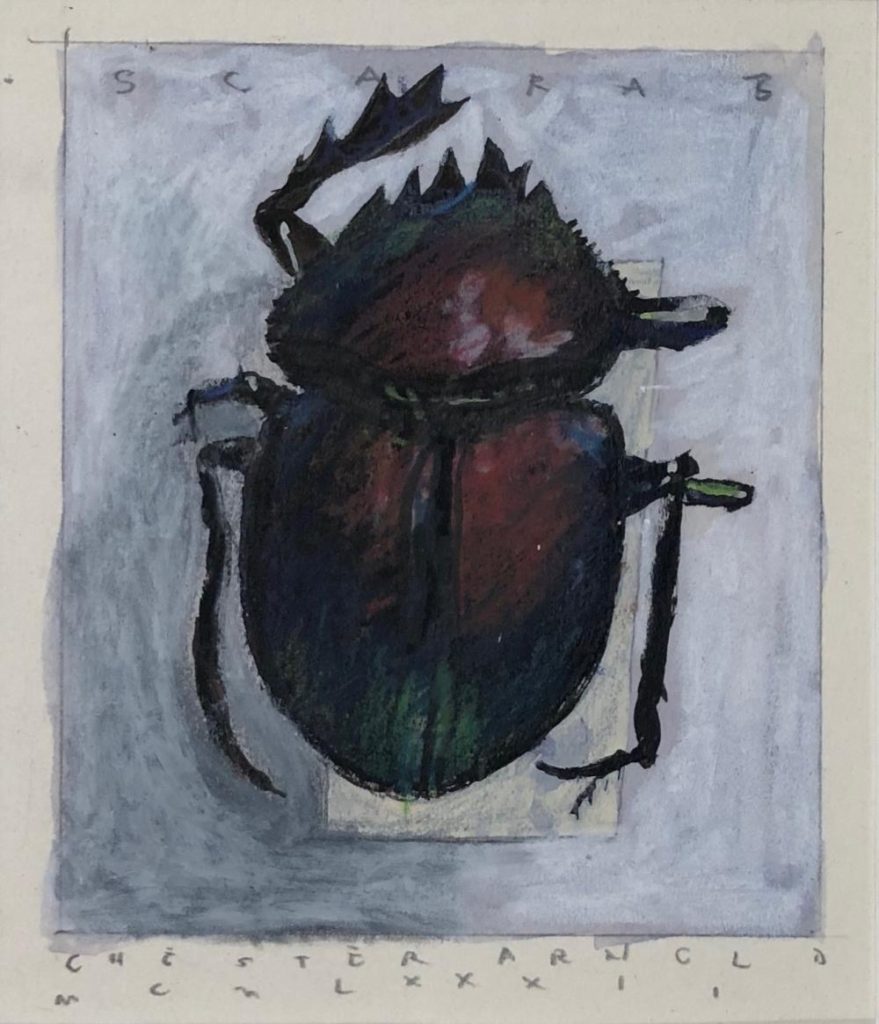

Sylvie nods. She looks to be in her early seventies. Her wedge of gray hair has grown out in odd ways since she’s been to the hairdresser, but she’s still put together. In that way she reminds Pina of her mother. She’s quite elegant, really, in a wool button-down blouse, a creamy shade of aubergine, and a straight black skirt. She stands with her legs crossed, apparently at her ease. Sylvie wears a pin on her blouse that Pina would love to see better, but she can’t get closer. It’s a black enamel scarab, beautifully dimpled over the body of the beetle, and set in old brass.

“By the way, I love your brooch.”

“Oh thank you. It’s Egyptian Revival, a gift from my husband forty years ago. It’s at least 110 years old, Edwardian, if the dealer is to be trusted. It’s really nothing more than a dung beetle, but the Egyptians held it sacred. The scarab shares a hieroglyphic with the early morning sun, if my memory serves me.”

“It’s marvelous.”

“The Egyptians believed that a scarab amulet brought luck.”

She wants to ask if this one brought Sylvie luck, but she keeps quiet.

“Oh, what a beautiful smile you have, Pina.”

She hadn’t known she was smiling. “Thank you.”

“I’m going to leave my scarab to you. I’ll write a very short codicil to my will.”

Pina nods her head reflexively a half dozen times; she’s just met the woman and she’s going to pass on her luck, good or bad. It’s seems a fair gamble is such an unlikely event transpired.

It’s an odd flirtation they’re having—mother and daughter? Pina’s curiosity gets the better of her and she asks a question that may be too forward: “How do you spend your days, Sylvie?”

“Reading. Reading and listening to music.”

“Funny, I never hear your music.”

“Headphones.”

She’d really like to ask Sylvie what’s prompted her bouts of crying, but that’s clearly a bridge too far. Instead: “And what do you read?”

Sylvie becomes animated. “I’m working my way through Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu in French. My mother was French and I grew up speaking it, but I’m afraid my French has faded over the years. It’s a bit of a struggle, but what else do I have to do? I’ve always wanted to make it through the whole thing. I will get through two books or three but I’ve never read all seven. Now I’m going to make it.” Sylvie has a cute gesture—wrinkling her nose after certain sentences, which has a way of brings a bit of lightness to her visage.

“Are you familiar with Proust’s À la recherché du temps perdu, Pina?”

“I know about it, but I’ve not read it. I’m sorry to say that I’m pretty much a philistine.”

Sylvie smiles at her tolerantly. “Proust has a character in the first book, a composer named Vinteuil, who’s written a sonata for violin and piano in F sharp minor, a little phrase of which sticks in the mind of the central character, Charles Swann.”

Pina realizes that Sylvie has probably not spoken to anyone face to face for weeks and she’s happy now to be a listener. How different from her drive to the city a few days ago with Charlie when she thought if he said any more she would have to scream.

“And every time Swann hears the phrase,” Sylvie says with a bouncing nod of her pointed chin, making sure she has a listener still, “every time he hears that musical phrase he becomes emotional. It brings him back particularly to his lost love Odette. For decades people have speculated about who Proust based the composer on. Camille Saint-Saëns is a popular choice, and the same can be said of César Franck, Gabriel Fauré, Claude Debussy, and even the Richard Wagner of Lohengrin. So, you see, I listen to all those composers as I read Proust. My son set-up Spotify for me, which I think is, frankly, one of the wonders of the world.”

“So have you figured out which composer the character is based on?”

“Oh, I’m glad you asked. There happens to be a lesser-known composer named Gabriel Pierné. The man was by no means obscure in the Paris of his time. Among other things he conducted the premiere of Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite with the Ballet Russes, and he has a square named after him in the Île-de-France. His Sonata for violin and piano in D minor, opus 36, composed in the year 1900, just might be what Proust had in mind. We’ll never know for sure.

“The funny thing is that the phrase catches in my brain as well. It comes early in the second movement, the allegretto tranquilo. The violin states it. Let me see if I can give you an idea.” With surprising alacrity, Sylvie hums the melody, articulating each note precisely. “You see, it’s really a folk melody. Nothing more.”

“Does hearing the phrase bring you back to anything, Sylvie?”

She sighs in a satisfying way. “Yes, it brings me back to who I want to be with.”

“Lovely, and to think you may have solved the puzzle about the composer.”

Sylvie’s hazel eyes brighten. “Yes, I may have. And now I’m getting close to the end of the seventh book.” She squints and her expression turns grim. “Each day I read a little less. It’s roughly 2,000 pages and I have only 200 pages left. I really don’t know what I’m going to do with myself when I finish À la recherche du temps perdu.”

“I’m sure you’ll find something else to read.”

“After Proust? I wonder.”

“It’s very nice to meet you, Sylvie.”

“And you too, Pina, and you too.”

Each evening she and Charlie make dinner together. He is a much more gifted and imaginative cook than she is and she has no problem at all serving as his sous chef. Tonight they prepare slow roasted lamb shanks and Pina takes pleasure chopping onions and herbs while drinking a fine Gruner Veltliner that Charlie had on ice. The last days, she’s been trying to imagine what sharing a life with Charlie would be like. It’s lovely to watch him standing at the stove, barefoot, in cargo shorts and an apron that reads: Country Master, as he braises the shanks, the fragrance of shallots, garlic, and charred meat, spilling through the kitchen.

He cranes his neck toward her. “Would you open the window, Pina?”

She does. “I know you, you want to share the great smell of our dinner with the neighbors.”

“Exactly.”

If she were to move in with Charlie she’d need to make peace with Roscoe. Charlie’s done a good job of keeping the bird in his own realm. He senses Pina’s ambivalence to the parrot, and she makes a point, in deference to Charlie, of always greeting the bird when she comes over. “Pina, Pina, Pina,” he says in his parrot bark, “where you beena?” Roscoe’s added a new trick phrase: “I’ve been thinking about you.” She wants to tell him not to bother.

Meanwhile, there’s some hope for Vince. Once he’s done detoxing, which should be soon, he’s scheduled to spend a month in a treatment facility in West Marin called Harmony Acres. The morning after Charlie took Vince to the hospital, she called Vince’s close friend Bernard and apprised him of what was going on. Since then Bernard has been a godsend, helping to make the arrangements at Harmony Acres and offering to drive Vince out to the Nicasio facility.

A psychiatrist at Kaiser, Bernard offered to take charge of the situation during the long conversation they had together. Pina revealed that it was unlikely she’d move back in with Vince. “I don’t want to live with an addict,” she said. She doesn’t need to tell Bernard that she has become very fond of another man or that she an Vince were already having problems. His addiction on top his philandering is more than she can fathom.

“But what,” Bernard asked in his posh English accent, “if Vince managed to get clean?”

“This is a little rough to say, Bernard, but I wouldn’t bet on his staying clean. I’m going to start looking for a new place to live because the place I’m staying in is his.”

Bernard, really a good friend to Vince, got her to agree to wait until Vince came out of recovery “before she did anything rash.” Pina likes Bernard and really appreciates what he is doing for Vince, and what he’s sparing her from having to do. And yet she felt obliged to describe the depth of Vince’s fall.

“Let me explain what it was like walking into the Liberty Street house, Bernard. What Vince did to that house was criminal.” She described in sordid detail what she encountered in the house that she’d called home for seven years.

“I can only imagine how you must feel, Pina. It must seem a harsh betrayal.”

“Yes, one of many.” In the end she relented. She wouldn’t do anything rash.

“The lamb shanks are in the oven,” Charlie announces, triumphantly. “We eat at ten o’clock, just like the Spaniards.”

“And what shall we do in the meantime?”

“Well, in keeping with the Spaniards, I think we should have a siesta, of sorts.”

“Of sorts?” she asks.

“In a manner of speaking.”

“So we shouldn’t expect much from this siesta?”

“It remains to be seen,” says Charlie. “We keep our expectations low and likely exceed them.”

“Is that your philosophy of life?”

“Pretty much.”

She walks behind him and unties his apron. Then she lifts his black Yosemite Park Half Dome t-shirt over his head and leaves a trail of kisses from his neck to his navel.

Charlie pulls her close. She loves the smell of him: a mélange of sandalwood body lotion, Arm & Hammer rosemary and lavender deodorant, and his native tang, which she can’t get enough of. Charlie kisses her sweetly at the corners of her mouth. “I think this is going to be the kind of siesta we like best.”

She wakes after Charlie to the smell of coffee. By the time she gets to the kitchen in her short kimono Charlie is truly angry. She’s never seen him like this. “It’s Memorial Day weekend,” he shouts, “with 100,000 dead, and this fucking asshole is out playing golf and tweeting personal attacks and conspiracy theories from his golf cart.”

She pours herself coffee. “And good morning to you.”

“I’m sorry, Pina. It just gets the better of me sometime and I need to blow off steam.”

“Please go on. It’s fine with me as long as you’re not aiming your anger at me.”

“At you, no way.” He gives her a big lollipop kiss on the lips, and then veers off into a more muted rant. “What percentage of those dead would still be alive with a competent leader?”

“A wild guess—50%.”

“You’re underestimating it, Pina.”

Charlie hustles out of the room, clearly on a mission.

She sits at the kitchen counter sipping coffee and dangling her legs. She wouldn’t mind a little Irish in her cup this morning. Take a nice hop into the day. Charlie has a bottle of Bushmills, she noted when she took inventory, but she doesn’t want to scandalize the man. As it is, she’s kept her imbibing to a minimum in his presence—no more than a bottle of wine a night, and a couple of snifters of cognac for the varnish. Now he’s been gone a while. She should have grabbed the Bushmills.

Charlie hurries back, doing the dance of a man with an open laptop and a cup of coffee.

“Charlie, why are you going back and forth with your coffee?”

“Thought I might want some. Got to stay agile.” He grins at her. The guy’s falling in love. That’s what she was afraid of.

“Look at this, Pina, look at this.” He crouches down beside her and cues up a video as well as the narration: “A mass of white people,” he says,” in a voice from an old newsreel. “Yes, very white people, no masks, keeping scant distance as they jump up and down in a pool the size of a valley, which looks like it might run to the River Jordan. These are the new liberators of our country.” She loves to see him get worked up and admires the humor he can bring to his earnestness. Pina doesn’t know if she has the heart left to be earnest.

“Look at them prance around in a sunken American petri dish under a massive flag.”

“Are they getting baptized?” she asks.

“They already have been. Make America Great Again.” Charlie’s brogue has become urbane like a voiceover by John Hamm on Madmen. She bets that Charlie’s an old Toastmaster.

“We must understand,” he says, “that this is Lake of the Ozarks, the Babylon of Missouri.”

“You mean the Ozarks are a real place?.”

“And look at this.” He starts up another video: “Very unpleasant. A trio of unmasked white women deliberately coughing in the face of a masked restaurant host.”

Pina shakes her head. “Who is this guy, Christ? Turning the other cheek. I would have smashed them.”

Charlie switches back to his newsreel delivery. “This is America 2020. The silent majority has finally discovered all its grievance and its moronic voice.”