MOURNING DOVES

Vince calls in the morning, all charm. She figures he’s probably mixed himself the right pharmaceutical cocktail. He’s always been something of a pharmacist, and probably didn’t sleep all night. Now she gets ten minutes of his groove time.

“Been listening to a lot of Trane,” he says. “Even when I’m not listening to Trane, I’m listening to Trane. Come home for six hours, maybe eat something, settle into my chair with the headphones. Put on my mix.”

“Your Trane mix.”

“Right. Maybe I sleep, maybe I don’t. But Trane . . .”

“Absorbing that much Trane is bound to change the timbre of your voice, the way you speak.” She’s playing with him now, just trying to goose his good mood.

“Damn right, he’s changing my sound. Can’t you hear it, Pina? My soaring speech.”

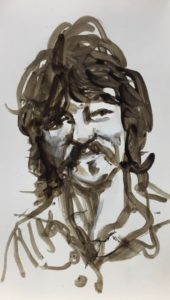

“I’m looking at Trane right now,” she says, her eyes locked with the sax man’s on his Blue Train cover. Were she to describe her communion with Coltrane, it might have more effect than phone sex.

“You’re looking at my man? Aw that’s awesome,” he says, before going on an amphetamine-laced tear: “How you doing, darling? What’s shaking? How’s your soul, and all that? Are you eating? Are you drinking? Are you sleeping? Are you jonsing for me?”

“Sorry, Vinnie,” she says with a laugh, “I don’t jones.”

“Come on, what’s the matter with you? Don’t tell me that you’re still reading The Plague.”

“Yeah, I’ve got it on a slow drip.”

“Listen,” he says, shifting down his motor voice with a graceful ritardando. “Something I’ve been meaning to mention. There’s this guy in the condo complex. Charlie. He gave me a call. Said he met you once. We went over to his place or something. Few years back. This I do not remember. But anyway, he heard you’re up there and said he’d be happy to shop for you any time. Says he doesn’t know what to do with himself and he likes to go shopping. Don’t worry; he’s a fastidious guy. Little bit of a square, but you don’t have to spend any time with him. You tell him what you want; he leaves it at the door. Next time you leave a check for him. Would give me a little peace of mind, Pina. I know you think you’re invulnerable, but all that asthma you had—this virus is looking especially for a host like you.”

At first Pina wonders if this is some kind of sick joke. Has Vince heard that she and Charlie have been flirting, or whatever it is they’re doing, with each other?

“So he wants your phone number. I wanted to check with you first. Don’t worry; Charlie won’t bug you. He’s just the Good Samaritan type.”

“Sure,” she says, “that’s nice of him. I think I remember him. He’s the guy that used to be called Raoul?”

“God, you have a memory, Pina. Here, take down his number.” He calls out some digits that she doesn’t even hear.

“Wait a minute, my pen didn’t work, Vince.” She jots the number down as he repeats it.

“So, I’ll give him your number, but you call him when you need something. Listen, I got to go.”

“Be safe, Vinnie.”

“Safety first, my love.”

Pina spends the next half hour circuiting the big room in a wash of guilt and exhilaration. To not reveal that she knows Charlie, and wants to know him better, means that she’s already cheating on Vince.

This morning she breaks her rule about boycotting any news item or opinion in which Trump is in the title. She can’t resist an article in The Guardian, headlined: Trump is Killing His Own Supporters, which suggests that “The Trump Organism is simply collapsing,” because of his inaction, particularly in allowing nine red states to remain open for business. The writer, Lloyd Green, rather nails it: “There’s nothing like populism marinated in wholesale contempt for the populace.”

Pina relishes the notion of Trump and his supporters, nonbelievers in the virus, succumbing to it. Has she become a sadist? Does she really want all these MAGA people to die? No, she’d be just as happy if they remained too sick to ever vote again.

The rest of the morning news glean is not so cheery: Domestic abuse hotlines, in the era of sheltering in place, exploding with calls for help; frontline medical staffs rushing to make out their wills; nearly every two minutes a New Yorker dies of Coronavirus. Every two minutes—she closes her eyes to try and grasp the enormity of that.

In Sonoma the birdsong is ubiquitous, but this morning she listens particularly to the mourning doves. They have a five-note song: ah-OOOOH-ooh-ooh-ooh. She never thought the mourning doves were actually mourning, but now she can hear it—they have been mourning all along as if they’ve known this was coming.

Her mood turns dark before she makes it through the morning. It had started out so promising with Trump killing his own people, after Charlie’s display of ingenuity, with Vince as his tool. But it seems craven, the more she thinks about it. Why did he have to bring Vince into it? What a time to humiliate a doctor, turning him into a cuckold.

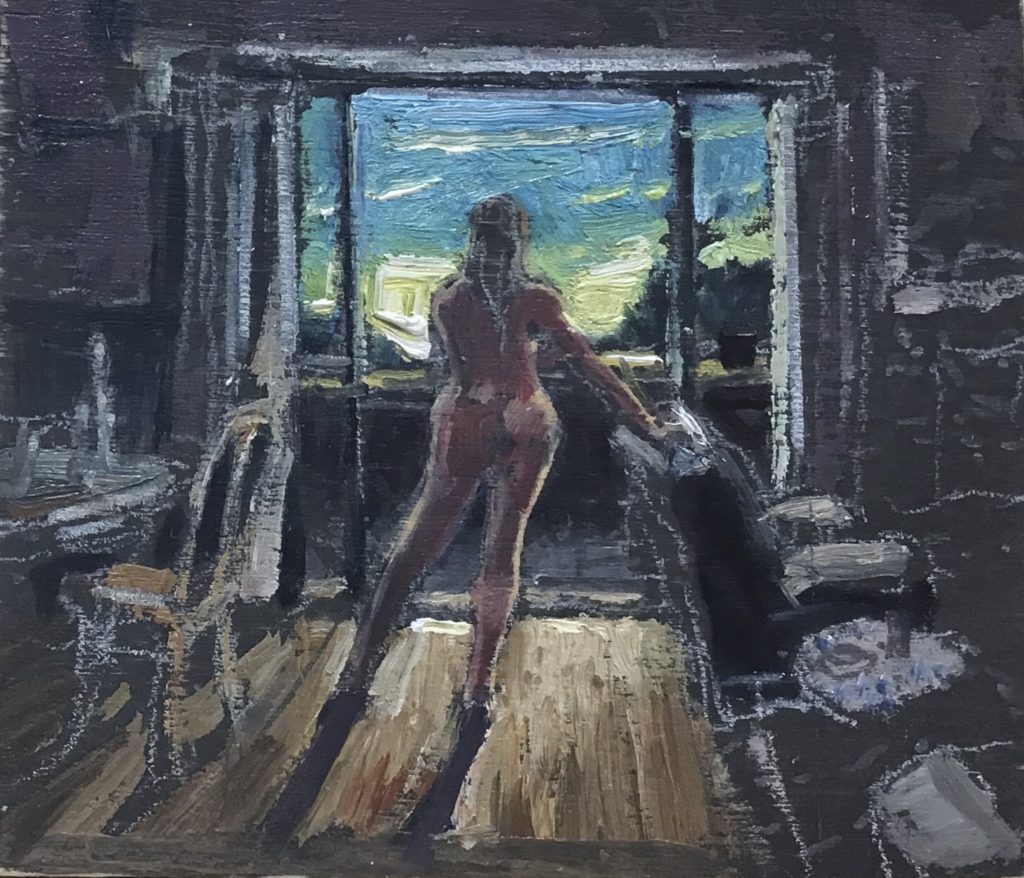

It spirals down from there. She’s followed the news too closely today—the talk of this isolation going on for months, years, as the virus mutates. She tries to imagine society on the other side: folks suspecting each other, no longer touching as we once did, a mass loneliness descending like a toxic cloud over the populace. And then her ideation shifts to suicide, not her own necessarily, but the likelihood that suicides, too, will become a vast statistic. As so many face staggering losses, personal and financial, why make the effort to rebuild a life and learn a new way to live with others?

She knows it’s stupid to go shopping given her mood, but she can’t stop herself. She’s not going to wait for Charlie to call and take her shopping order. She’d just as soon tell Charlie to go to hell.

She’s done pretty well to last more than three weeks on her initial horde. For the first time, she dons one of the N95 masks Vince sent her off with. It’s politically incorrect to wear one, she knows. They’re supposed to be reserved for the frontline medical folks. Vince bought a box of them a couple of years ago when the fires were bad, and nobody’s going to accept hers from an opened box.

She heads to Whole Foods, the Sonoma version of which generally feels like a walk in the country compared to the San Francisco stores. She’s surprised how empty the parking lot is. Apparently the masses come early. Two employees meet her at the door, one tells her that she can no longer use the bags she’s brought, while the other does a showy job of sanitizing the cart for her. And away she goes. The store is nearly vacant, with three employees for every customer; it almost feels like she’s on a reality show. Reality—what the hell does that mean?

She grabs fruits and vegetables in a flurry, and has to remind herself that this isn’t a timed event, and yet being in public, with all these germs lurking everywhere, keeps her doing her Energizer bunny thing. Pina knows that the butchers, standing in their too-white-to be-real aprons, are actually covered in germs, so she heads to the frozen section, where she plucks a two-pound bag of jumbo shrimp, some salmon steaks, and an ugly stack of hamburger patties, from the arctic chambers.

She snatches so many Imagine soups, that she’s sure the unconscious has foisted a plan—broths and bisques and minestrones are all she’ll be able to get down during her demise. She captures tins of tuna, jars of cornichons and martini olives. Which brings her to liquor. After adding a few bottles to her cart, she looks all over the place for a fucking bottle of Campari.

A skinny boy-clerk standing nearby, with what Vince would call a shit-eating grin on his face, asks if he can help her find anything.

“Campari. Where the heck do you keep the Campari?”

“I’m so sorry,” he says, “we don’t stock it because it’s made with red dye 40.”

His superciliousness is so pronounced, she’d like to wash his little turd-boy mouth out with soap. “How am I supposed to make a Negroni?”

“I can’t tell you that. I stick to beer.”

“And they have you managing the liquor section?”

“Oh, I’m not the manager. I just . . .”

Pina leaves him talking while she wheels away, wondering if she’s had her last Negroni.

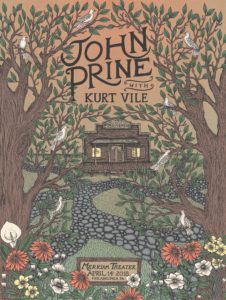

On the drive home she hears that John Prine has died. It had sounded like he was getting better. She heard him a couple of times at Hardly Strictly Bluegrass in Golden Park and started listening to him regularly. His quirky, soulful lyrics made her feel like he was a member of her family.

Hardly Strictly was an annual even she looked forward to. Vince couldn’t stand the crowds so she often went alone. Her slenderness was an asset as she knifed her way to the front of stages, smiling at everybody around her, offering people drinks from her twist cap bottle of zinfandel, or a hit off a joint. She ate fried chicken and pork buns from strangers. Her personality changed those weekends when she enjoyed being a member of the human tribe, in the middle of such good cheer and musical majesty. Now Hardly Strictly, always the first weekend of October, will be a casualty.

Maybe it was the second or third time she went that she heard John Prine sing “Angel from Montgomery.” She’d found a spot on the grass, three rows from the stage and got a good look at his red swollen hands, fingerpicking, rings on the left hand fingers, picks on the right, his muscle memory, it seemed to her, magic. And then he opened his mouth, his face sunken on the left side; his voice, a whole wagon of sound, started up a half step and bent back down. The surprise of the first line, “I am an old woman, named after my mother,” with some laughter on the ground of Speedway Meadows, and then a stillness to match Prine’s quiet gravity. To Pina, he looked plain as anybody, like he might have been in the late prime of his second life. He could have been Everyman. By the time he sang the chorus for the third time, she was singing with him.

Make me an angel that flies from Montgomery

Make me a poster of an old rodeo

Just give me one thing that I can hold on to

To believe in this living is just a hard way to go.

Out on the deck this evening, Pina listens closely to a mourning dove’s three-note song, two quick eighth notes, followed by a languorous quarter. The dove repeats the pattern seven times, as if somebody has wound her up. The long pause after the repetitions allows it to sink in. There are worse things than mourning. Pina knows how grief can become healing. She closes her eyes and listens to the mourning dove.