Over the course of her five-decade career, Viola Frey produced an impressive body of artwork, including ceramic sculpture, bronze sculpture, paintings, and drawings, and explored the mediums of glass, wallpaper, and photography. Internationally respected—with works held in over seventy public collections—Frey was drawn to the expressive potential of clay and, along with her colleagues Robert Arneson and Peter Voulkos, instrumental in cracking the barrier between craft and fine art.

Born in 1933 and raised on her family’s vineyard in Lodi, California, Frey felt compelled to create and exhibit artwork at an early age. After graduating high school in 1951, Frey took classes at Stockton College (now San Joaquin Delta College) before receiving a scholarship to attend the California College of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts) in Oakland. She completed her BFA in 1955 and then traveled to New Orleans to pursue an MFA at Tulane University. While there, she studied under George Rickey, Katherine Choy, and visiting artist Mark Rothko. In 1957, before finishing her graduate degree, Frey moved to New York, where Choy had recently founded the Clay Art Center in Port Chester and was actively engaged with the advancement of ceramic arts. To support herself, Frey commuted into Manhattan daily and worked in the business office of the Museum of Modern Art.

By 1960 Frey had returned to San Francisco, where figurative art and working with clay were in the vanguard. During this period, she produced functional pottery, wall plates, and ceramic sculpture, in addition to continuing a rigorous painting and drawing practice that focused on still-life, landscape, and figural compositions. In 1964 she was hired at CCAC, at first as an Artist Potter in Residence and later taught a color and light class in the Painting Department. When reflecting on her early teaching years, she mentioned particularly enjoying the freedom to work in all mediums. Frey felt that “the only way to establish oneself as an artist was to show that as an artist [she] was multifaceted and that [she] could work in other media. So no one could put [her] in a box.”

Viola Frey with her dog outside her Oakland Avenue studio, Oakland, California, 1983. Photograph by M. Lee Fatherree.

whiteware and glazes | 70 . x 53 . x 43 . inches (179.1 x 135.9 x 110.5 cm) | ALF no. VF-0045CS

Artists’ Legacy Foundation, Oakland, CA | Photograph by M. Lee Fatherree

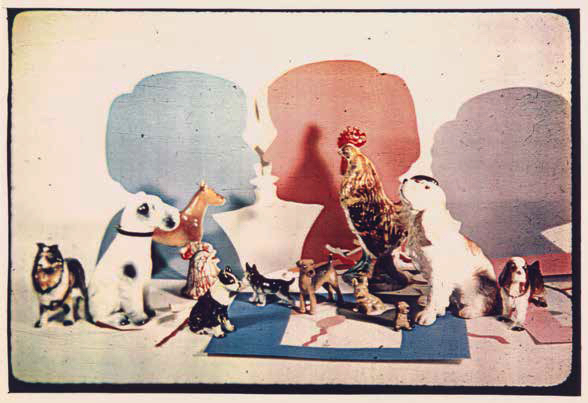

Frey was a passionate collector. Along with fine art, china, and books, she collected figurines and knick-knacks found at flea markets, which served as inspiration for her junk sculptures, later called “bricolages.” By curating and producing her own source materials, Frey created a complex personal iconography that would serve as her creative wellspring throughout her artistic career and assist in her exploration of power and gender dynamics.

In 1975 Frey moved from San Francisco to Oakland, where she could expand her studio outside and study how natural light would interact with the commercial glazes that she preferred. As her figures became more colorful and increasingly taller—eventually reaching over 10 feet—her need for space grew. In 1996 she purchased a 14,000-squarefoot warehouse, where she worked until the day of her death July 26, 2004.

Prior to her death, Frey exhibited annually, traveled the world to expand her art practice, received two National Endowment for the Arts fellowships, taught thousands of students, guided the design and building of the Noni Eccles Treadwell Ceramic Arts Center on CCAC’s Oakland campus, was honored with an honorary doctorate from CCAC, and co-founded Artists’ Legacy Foundation.

Learn more about her work and accomplishments at violafrey.org and artistslegacyfoundation.org

An excerpt from Susan Griffin’s essay:

Certainly, Frey undermines conventional notions about gender (as she chips away so many presuppositions). But beware of jumping to conclusions. Her work does not engage directly in feminist polemics. Did she ever call herself a feminist? The question seems irrelevant or at the very least ahistorical for an artist who was born in 1933. Like Joan Didion, Sylvia Plath, Doris Lessing, Lorraine Hansberry, or Louise Nevelson, she belongs to an earlier generation of women, who, willingly or not, inspired my generation by refusing to submit to the command, so insistent in the fifties, that they spend their time performing domestic tasks.

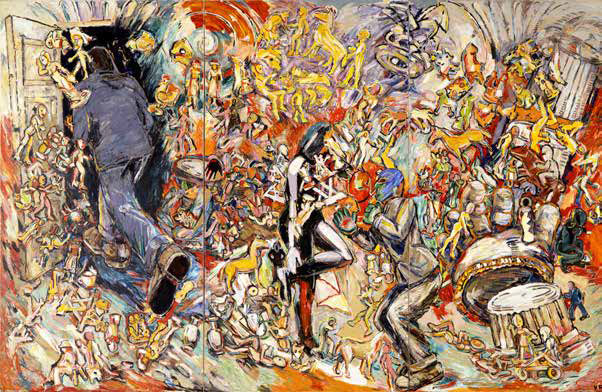

alkyd oil on canvas | 105 x 163 inches (266.7 x 414 cm)

ALF no. VF-0089PT | Artists’ Legacy Foundation, Oakland, CA

Frey’s work in the world was to make art, to mine meanings that cannot be found in any established terminology, argument, or conceptual map. Her sculptures, ceramics, paintings, photographs travel into subterranean regions, beyond what is ordinarily understood about our shared culture or even within more private realms of the psyche.

Though with her lifelong habit of reading (as a child she read through the books titled A through Z in the Lodi public library) and a sharply curious mind, she was influenced by many thinkers, her work—as she described her process—originated less from ideas than from her hands. Her hands pinching the edges of clay together, for instance, to make the ceramic pieces out of which she would eventually build towering sculptures. In this way she could explore the clay and, I might add, the hidden contours of her own mind.

Of course, as with any artistic work, she often started with concepts about the work too, but one senses from her remarks that instead of proceeding from any theoretical formulation, she usually began by imagining what she might construct and how. As when she wrote in a letter, “Next project in mind, a sculpture six feet high to be constructed in sections…based on the human figure, of course.” And there was this too, as she once said in a long interview: “clay was a wonderful material to be stuck in, because you could find your way, your own way. There was no one to tell us what to do.”

Read the full essay: If the Clothes Fit

electrostatic print | 7 7/8 x 9 15/16 inches (20 x 25.2 cm) | ALF no. VF-5539PH

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Garth Clark and Mark Del Vecchio Collection, museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess

Law Accessions Endowment Fund, 2007.859.4 | Image courtesy The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston